Background Science

Classification of Comets

How to name a comet

A new cometary designation system was adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in August 1994, and took effect at the beginning of 1995.

The principal designations for discoveries of comets, according to the Catalogue of Cometary Orbits, consist of the year and an upper-case letter to indicate the half-month of discovery in that year, so:

A = Jan 1-15

B = Jan 16-31

C = Feb 1-15, ..., Y = Dec 16-31

(I is omitted to avoid confusion)

followed by a numeral showing the order of announcement of discovery in that half-month.

The half-months are as used for discoveries of minor planets, the difference being that minor-planet designations have a second letter (as well as possible numerals) to indicate the order of discovery announcement.

'Discovery' refers to the time when the discovery observation is actually made (and in the case of a photographic observation, for example, it is usually the time of mid-exposure), even though the comet might not actually be recognized until long afterward. Unlike that for minor planets, the cometary system is precisely the same for comets discovered before and after 1925 (Universal Time is used in either case), with the usual astronomical convention of using the Julian calendar before October 1582 and the Gregorian calendar afterward.

The new cometary designations are mainly prefixed by:

- P/ for 'short' period comet

- C/ otherwise

More rarely:

- D/ considered defunct - i.e. it would be ill-advised seriously to consider a prediction for a future return, because either it is known no longer to exist, or it has failed to show at several expected returns, or because its orbit is poorly known.

- A/ would be used to denote an object given cometary designation but deemed to be a minor planet (no examples so far).

- X/ is used for comets for which it is not possible to compute orbits - and that in some cases may never even have existed.

Why Comet 46 P/Wirtanen?

When the periodicity of a comet is well-established, either because of a recovery or an identification at a second passage through perihelion, this is shown by assigning a sequential periodic-comet number, which normally appears in front of the P/ (or D/) prefix.

There is also the possibility of assigning such a number to a comet, if and when it is observed through its first aphelion passage after discovery. An attempt has been made to assign these periodic comet numbers in a historically meaningful manner (e.g. 1 P/Halley, 2 P/Encke, etc), to allow continuity between past and future returns. Thus Comet Wirtanen was the 46th periodic comet to be assigned a number in this way.

Components of comets that are observed to split are indicated by -A, -B, etc after the P/ (or D/) number.

Why a new system?

The new system abandons the tradition, introduced by the Astronomische Nachrichten in 1846, of applying Roman numerals to comets in the order they were observed to pass perihelion in a particular year. In practice this proved troublesome. A subsidiary system, adopted by the Astronomische Nachrichten in 1870, which assigned lower-case letters to comets in order of announcement of discovery in a particular year, was applied too erratically, with different letters, or no letter at all, being assigned to the same comet. In reality, a substantial fraction of both Roman numeral and letter designations had come to be applied not to discoveries, but to recoveries of periodic comets on subsequent perihelion passages.

It was felt that a modern designation system should generally restrict acknowledgement of recoveries to those comets making their first predicted returns (when the error is expected to be greatest).

Finally, the distinction between a comet and a minor planet is often quite unclear, whether considered in terms of particular observations or of the general evolution of the solar system. It was therefore felt that any new cometary designation system should be more similar to that used for minor planets.

Taken from the tenth edition of the Catalogue of Cometary Orbits, by B.G. Marsden and G.V. Williams, available from the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center:

Minor Planet Center

Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

60 Garden Street

Cambridge, MA 02138

USA

Past Missions to Study Comets

Launch 12 August 1978: International Cometary Explorer

|

|

ICE, NASA/JPL/CalTech |

International Cometary Explorer (ICE) achieved the first ever comet encounter. This NASA spacecraft was originally known as ISEE-3 (International Sun-Earth Explorer). Having completed its original mission, it was reactivated and diverted to pass through the tail of Comet Giacobini-Zinner on 11 September 1985. It also observed Comet Halley from a distance of 28 million km in March 1986.

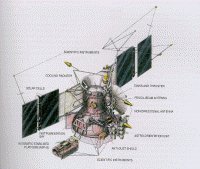

Launch 15 and 20 December 1984: Vega-1 and Vega-2

|

|

Vega-1 |

Vega-1 and Vega-2, two Russian probes, each left a lander on the surface of Venus as they flew past it on the way to investigate and photograph Comet Halley. Both spacecraft imaged the comet's nucleus, while other experiments studied its nearby dust, plasma, gas, energetic particles and magnetic field. Vega-1 made its closest approach to the comet on 6 March 1986 at a distance of 8890 km. Vega-2 flew to within 8030 km of the comet's nucleus on 9 March 1986.

Launch 8 January 1985 and 19 August 1985: Sakigake and Suisei

|

|

|

Sakigake |

Suisei |

Sakigake and Suisei were Japan's first deep space missions. Suisei approached to within 151 000 km of Comet Halley on 8 March 1986 to observe its interactions with the solar wind. Sakigake approached to within 7 million km of the comet on 11 March 1986 in order to study radio and plasma waves.

Launch 2 July 1985: Giotto

|

|

|

Giotto |

Comet Halley's nucleus |

Giotto obtained the closest pictures ever taken of a comet at that time. This European Space Agency spacecraft flew past the nucleus of Comet Halley at a distance of less than 600 km on 13 March 1986. Images showed a black, potato-shaped object with active regions which were firing jets of gas and dust into space. Giotto then became the first spacecraft to visit two comets when it passed within 200 km of Comet Grigg-Skjellerup on 10 July 1992. It was placed in hibernation on 23 July 1992, and the spacecraft has since been inactive. Giotto returned to the vicinity of the Earth on 1 July 1999. The distance of its closest approach was very uncertain, the estimate being about 220 000 km, just over half the Earth-Moon distance. No communication with the spacecraft took place at this time. Giotto will continue to orbit the Sun for the foreseeable future, completing six revolutions roughly every seven years.

Launch 25 October 1998: Deep Space 1

|

|

Deep Space 1, NASA/JPL/CalTech |

Deep Space 1 (DS1) was the first spacecraft in NASA's New Millennium programme. Its primary mission was to test 12 new advanced technologies, particularly ion propulsion. Most of these technologies were validated during the first few months of flight. It then approached to within 26 km of asteroid 9969 Braille on 28 July 1999. The few pictures returned showed that Braille measures about 2.2 km across by 1 km.

Despite the loss of its star tracker navigation system, the mission was extended and Deep Space 1 completed a successful flyby of Comet Borrelly on 22 September 2001, passing within 2200 km of the comet. Analysis of the 30 or so black and white pictures of the bowling-pin-shaped nucleus showed that it was about 8 km long. Other instruments examined the gas and dust in the surrounding coma and studied the interaction of the comet with the solar wind. DS1 found that the nucleus was not in the centre of the coma, as expected. The coma's 'lopsided' shape was due to a huge jet of material that was shooting into space from one side of the nucleus.

Deep Space 1's mission came to an end on 18 December 2001 when its ion engine was turned off.

Launch 3 July 2002: Comet Nucleus Tour (CONTOUR)

Comet Nucleus Tour.

(Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/Cornell.)

Comet Nucleus Tour (CONTOUR) was a NASA Discovery mission to improve our understanding of comet nuclei. Encounters were planned with Comets Encke (12 November 2003) and Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 (19 June 2006). CONTOUR could also have added an encounter with a 'new' comet from the outer Solar System if one had been discovered in time for the spacecraft to fly past it.

Following the firing of the rockets, contact with the spacecraft was lost. The search for CONTOUR was abandoned in December 2002.

Current and Future Missions to Study Comets

Launch 7 February 1999: Stardust

|

|

Stardust |

Stardust is a NASA Discovery mission. It will travel into the coma - the cloud of ice and dust that surrounds the nucleus of Comet Wild-2 - coming to within 150 km of the nucleus itself on 2 January 2004. There, it will gather comet dust particles and deliver them back to Earth. En route to the comet, Stardust will attempt to capture interstellar particles that are believed to have entered our Solar System. The mission is scheduled to end in January 2006, when the Stardust sample return capsule will return to Earth and parachute to a designated landing spot in the Utah desert.

Launch 2 March 2004: Rosetta

|

|

Rosetta |

Rosetta is an ESA cornerstone mission that was originally scheduled for launch in 2003. It will study the nucleus of a comet and its environment in great detail. The prime scientific objective of the Rosetta mission is to study the origin of comets, the relationship between cometary and interstellar material and its implications with regard to the origin of the Solar System. The Rosetta lander will land on the comet nucleus and will focus on the in situ study of the composition and structure of the nucleus material.

Launch January 2005: Deep Impact

|

|

Deep Impact |

Deep Impact is a NASA Discovery mission to Comet Tempel 1. It consists of two craft that will separate when the comet is reached. The main spacecraft is an instrument platform that will fly slowly by the comet and record visual images and infrared spectral mapping data of the comet. The second craft is the 350 kg copper 'impactor', which will separate from the flyby craft and be propelled into a target site on the sunlit side of the comet on 4 July 2005. It will crash into the sunny side of the comet's nucleus at 10 km per second, creating a crater which is 120 m across and 25 m deep. This will be the first time any man-made object has impacted with a comet. Cameras and other instruments on the flyby craft and back on Earth will study the new crater and ejected material created by the impact.