Hubble reveals most detailed exoplanet weather map ever [heic1422]

9 October 2014

A team of scientists using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have made the most detailed map ever of the temperature of an exoplanet's atmosphere, and traced the amount of water it contains. The planet targeted for both of the investigations was the hot-Jupiter exoplanet WASP-43b.WASP-43b is a planet the size of Jupiter but with double the mass and an orbit much closer to its parent star than any planet in the Solar System. It has one of the shortest years ever measured for an exoplanet of its size – lasting just 19 hours.

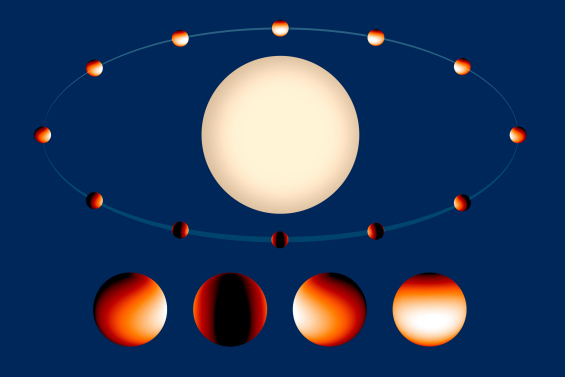

A team of astronomers working on two companion studies have now created detailed weather maps of WASP-43b. One study mapped the temperature at different layers in the planet's atmosphere, and the other traced the amount and distribution of water vapour within it – detail is shown in the video created by the team.

"Our observations are the first of their kind in terms of providing a two-dimensional map of the planet's thermal structure," said Kevin Stevenson from University of Chicago, USA, lead author of the thermal map study. "These maps can be used to constrain circulation models that predict how heat is transported from an exoplanet's hot day side to its cool night side."

The planet has different sides for day and night because it is tidally locked, meaning that it keeps one hemisphere facing the star, just as the Moon keeps one face toward Earth. The Hubble observations show that the exoplanet has winds that howl at the speed of sound from a day side that is hot enough to melt iron – soaring above 1500 degrees Celsius – to the pitch-black night side that sees temperatures plunge to a comparatively cool 500 degrees Celsius.

To study the atmosphere of WASP-43b the team combined two previous methods of analysing exoplanets for the first time.

By looking at how the parent star's light filtered through the planet's atmosphere – a technique called transmission spectroscopy – they determined the water abundance of the atmosphere on the boundary between the day and night hemispheres.

In order to make the map more detailed the team also measured the water abundances and temperatures at different longitudes. To do this they took advantage of the precision and stability of Hubble's instruments to subtract more than 99.95% of the light from the parent star, allowing them to study the light coming from the planet itself – a technique called emission spectroscopy. By doing this at different points of the planet's orbit around the parent star they could map the atmosphere across its longitude.

"We have been able to observe three complete rotations – three years for this distant planet – during a span of just four days," explained Jacob Bean from the University of Chicago, USA, leader of the research project. "This was essential in allowing us to create the first full temperature map for an exoplanet and to probe its atmosphere to find out which elements it held and where."

Finding the proportions of the different elements in planetary atmospheres provides vital clues to understanding how planets formed.

"Because there's no planet with these tortured conditions in the Solar System, characterising the atmosphere of such a bizarre world provides a unique laboratory with which to acquire a better understanding of planet formation and planetary physics," said Nikku Madhusudhan of Cambridge University, UK, co-author of both studies. "In this case the discovery fits well with pre-existing models of how such planets behave."

The team found that WASP-43b reflected very little of its host star's light. An atmosphere like that on Earth, with clouds that reflect most of the sunlight, is not present on WASP-43b, but the team did find water vapour in the planet's atmosphere.

"The planet is so hot that all the water in its atmosphere is vapourised, rather than condensed into the icy clouds we find on Jupiter," said team member Laura Kreidberg of the University of Chicago, lead author of the study mapping water on the planet. Kreidberg describes both results in her online video.

Water is thought to play an important role in the formation of giant planets. Astronomers theorise that comet-like bodies bombard young planets, delivering most of the water and other molecules that we observe. However, the water abundances in the giant planets of the Solar System are poorly known because water is locked away as ice, deep in their atmospheres which makes it difficult to identify.

"Space probes have not been able to penetrate deep enough into Jupiter's atmosphere to obtain a clear measurement of its water abundance. But this giant planet is different," added Derek Homeier of the École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, France, co-author of the studies. "WASP-43b's water is in the form of a vapour that can be much more easily traced. So we could not only find it, we were able to directly measure how much there is and test for variations along the planet's longitude."

In WASP-43b the team found the same amount of water as we would expect for an object with the same chemical composition as the Sun.

"This tells us something fundamental about how the planet formed," added Kreidberg. "Next, we aim to make water-abundance measurements for different planets to explore their chemical abundances and learn more about how planets of different sizes and types come to form around our own Sun and the stars beyond it." [1]

The results are presented in two new papers, one on the thermal mapping of the planet's atmosphere – published online in Science Express on 9 October – and the other on mapping the water content of the atmosphere – published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on 12 September 2014.

Notes

[1] Hubble's planned successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, will be able to not only measure water abundances, but also the abundances of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ammonia and methane, depending on the planet's temperature.

Notes for Editors

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between ESA and NASA.

The international team of astronomers in these two studies consists of: L. Kreidberg (University of Chicago, USA); J. Bean(University of Chicago, USA); J-M. Desert (University of Colorado, USA); M.R. Line (University of California, USA); J.J. Fortney(University of California, USA); N. Madhusudhan (University of Cambridge, UK); K.B. Stevenson (University of Chicago, USA); A.P. Showman (The University of Arizona, USA); D. Charbonneau (Harvard University, USA); P.R. McCullough (Space Telescope Science Institute, USA); S. Seager (Massachussetts Insitute of Technology, USA); A. Burrows (Princeton University, USA); G.W. Henry (Tennessee State University, USA), M.Williamson(Tennessee State University, USA); T. Kataria (The University of Arizona, USA) & D. Homeier (CRAL/École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, France).

Contacts

Derek Homeier

CRAL/École Normale Supérieure de Lyon

Lyon, France

Tel: + 33 47272-8894

Cell: +33 695 57 63 55

Email: derek.homeier![]() ens-lyon.fr

ens-lyon.fr

Nikku Madhusudhan

University of Cambridge

United Kingdom

Tel: +1 617 475 5112

Cell: +44 7804 419140

Email: nmadhu![]() ast.cam.ac.uk

ast.cam.ac.uk

Kevin Stevenson

University of Chicago

USA

Tel: +1 407-668-5698

Email: kbs![]() uchicago.edu

uchicago.edu

Laura Kreidberg

University of Chicago

USA

Email: kreidberg![]() uchicago.edu

uchicago.edu

Jacob Bean

University of Chicago

USA

Tel: +1 773 702 9568

Email: jbean![]() oddjob.uchicago.edu

oddjob.uchicago.edu

Georgia Bladon

ESA/Hubble, Public Information Officer

Garching, Germany

Tel: +44 7816291261

Email: gbladon![]() partner.eso.org

partner.eso.org