Hubble makes the first observation of a total lunar eclipse by a space telescope [heic2013]

6 August 2020

Taking advantage of a total lunar eclipse, astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have detected ozone in Earth's atmosphere. This method serves as a proxy for how they will observe Earth-like planets around other stars in the search for life. This is the first time a total lunar eclipse was captured from a space telescope and the first time such an eclipse has been studied in ultraviolet wavelengths. |

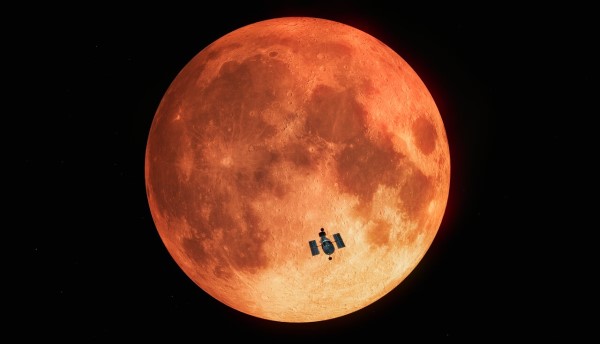

| Hubble observes the total lunar eclipse. Credit: ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser, CC BY 4.0 |

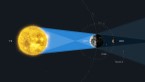

To prepare for exoplanet research with bigger telescopes that are currently in development, astronomers decided to conduct experiments much closer to home, on the only known inhabited terrestrial planet: Earth. Our planet's perfect alignment with the Sun and Moon during a total lunar eclipse mimics the geometry of a transiting terrestrial planet with its star. In a new study, Hubble did not look at Earth directly. Instead, astronomers used the Moon as a mirror that reflects the sunlight that has been filtered through Earth's atmosphere. Using a space telescope for eclipse observations is cleaner than ground-based studies because the data is not contaminated by looking through Earth's atmosphere.

These observations were particularly challenging because just before the eclipse the Moon is very bright, and its surface is not a perfect reflector since it's mottled with bright and dark areas. Furthermore, the Moon is so close to Earth that Hubble had to try and keep a steady eye on one select region, to precisely track the Moon's motion relative to the space observatory. It is for these reasons that Hubble is very rarely pointed at the Moon.

The measurements detected the strong spectral fingerprint of ozone, a key prerequisite for the presence – and possible evolution – of life as we know it in an exo-Earth. Although some ozone signatures had been detected in previous ground-based observations during lunar eclipses, Hubble's study represents the strongest detection of the molecule to date because it can look at the ultraviolet light, which is absorbed by our atmosphere and does not reach the ground. On Earth, photosynthesis over billions of years is responsible for our planet's high oxygen levels and thick ozone layer. Only 600 million years ago Earth's atmosphere had built up enough ozone to shield life from the Sun's lethal ultraviolet radiation. That made it safe for the first land-based life to migrate out of our oceans.

"Finding ozone in the spectrum of an exo-Earth would be significant because it is a photochemical byproduct of molecular oxygen, which is a byproduct of life," explained Allison Youngblood of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics in Colorado, USA, lead researcher of Hubble's observations.

Hubble recorded ozone's ultraviolet spectral signature imprinted on sunlight that filtered through Earth's atmosphere during a lunar eclipse that occurred on 20-21 January, 2019. Several other telescopes also made spectroscopic observations at other wavelengths during the eclipse, searching for more of Earth's life-nurturing ingredients, such as oxygen, methane, water, and carbon monoxide.

"To fully characterize exoplanets, we will ideally use a variety of techniques and wavelengths," explained team member Antonio Garcia Munoz of the Technische Universität Berlin in Germany. "This investigation clearly highlights the benefits of the ultraviolet spectroscopy in the characterization of exoplanets. It also demonstrates the importance of testing innovative ideas and methodologies with the only habitable planet that we know of to date!"

The atmospheres of some exoplanets can be probed when the alien world passes across the face of its parent star, during a so-called transit. During a transit, starlight filters through the backlit exoplanet's atmosphere. If viewed close up, the planet's silhouette would look like it had a thin, glowing "halo" around it caused by the illuminated atmosphere, just as Earth does when seen from space.

Chemicals in the atmosphere leave their telltale signature by filtering out certain colors of starlight. The spectroscopy of transiting planets' atmospheres was pioneered by Hubble astronomers. This was especially innovative because extrasolar planets had not yet been discovered when Hubble was launched in 1990. Therefore, the space observatory was not initially designed for such experiments. So far, astronomers have used Hubble to observe the atmospheres of gas giant planets that transit their stars. But terrestrial planets are much smaller objects and their atmosphere thinner. Therefore, analyzing these signatures is much harder.

That's why researchers will need space telescopes much larger than Hubble to collect the feeble starlight passing through these small planets' atmospheres during a transit. These telescopes will need to observe planets for a longer period, many dozens of hours, to build up a strong signal. For Youngblood's study, Hubble spent five hours collecting data throughout the various phases of the lunar eclipse.

Finding ozone in the skies of a terrestrial extrasolar planet does not guarantee that life exists on the surface. "You would need other spectral signatures in addition to ozone to conclude that there was life on the planet, and these signatures cannot be seen in ultraviolet light," Youngblood said.

Astronomers must search for a combination of biosignatures, such as ozone and methane, when exploring the possibilities of life. A multiwavelength campaign is needed because many biosignatures–ozone, for example–are more easily detected at specific wavelengths. Astronomers searching for ozone also must consider that it builds up over time as a planet evolves. About 2 billion years ago on Earth, the ozone was a fraction of what it is now.

The upcoming NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, an infrared observatory scheduled to launch in 2021, will be able to penetrate deep into a planet's atmosphere to detect methane and oxygen.

"We expect JWST to push the technique of transmission spectroscopy of exoplanet atmospheres to unprecedented limits," added Garcia Munoz. "In particular, it will have the capacity to detect methane and oxygen in the atmospheres of planets orbiting nearby, small-sized stars. This will open the field of atmospheric characterization to increasingly smaller exoplanets."

Notes

[1] This study's paper will appear in the Astronomical Journal.

Contacts

Allison Youngblood

Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics

Boulder, USA

Email: allison.youngblood lasp.colorado.edu

lasp.colorado.edu

Antonio Garcia Munoz

Technische Universität Berlin

Berlin, Germany

Email: garciamunoz astro.physik.tu-berlin.de

astro.physik.tu-berlin.de

Bethany Downer

ESA/Hubble, Public Information Officer

Garching, Germany

Email: Bethany.Downer partner.eso.org

partner.eso.org