#2: Solar Orbiter receives its sunblock

14 December 2018

It's testing time for ESA's Solar Orbiter: after leaving the premises of prime contractor Airbus Defence and Space in Stevenage, UK in September, the spacecraft has started its test campaign at the IABG facility in Ottobrunn, Germany. |

| Solar Orbiter at Airbus Defence and Space, Stevenage, UK. Credit: Airbus Defence and Space |

With its assembly completed, the Solar Orbiter Proto Flight Model (PFM) was despatched to Germany on 26 September. Since arrival there, it has been blanketed with layers of insulation in preparation for its first major environmental check-outs: the thermal-vacuum cycling and balance tests. These will ensure that the spacecraft can carry out its ambitious mission to study the Sun close up.

The PFM is essentially the same as what is referred to as a Flight Model (FM) in the case of other missions, but it is subjected to more severe testing environments in order to complete its qualification campaign.

The first major activity to take place after the PFM's arrival at IABG was the installation of 10 radiator panels for the instruments on one of the side faces of the spacecraft – the one hosting the payload panel. The integration lasted two weeks and involved many complex tasks that were performed by specialist staff from RUAG Space and Airbus-Stevenage.

Before leaving the UK, only some portions of the spacecraft had been fitted with the multi-layer insulation (MLI) needed to protect it from the extreme temperatures it will encounter in the Sun's vicinity. During October and November, the remaining insulation blankets were attached all over the exterior of the spacecraft's platform, with some 350 pieces used on the instrument radiators and another 200 on the rest of the spacecraft.

Meanwhile, a protective heat shield and four communications antennas – a 1.08-m diameter high-gain antenna for primary deep space communications, a medium-gain antenna and two low-gain antennas – were also integrated on the PFM during the second half of October.

|

| Solar Orbiter after installation of multi-layer insulation and radiators at the IABG facility in Ottobrunn, Germany. Credit: Airbus Defence and Space |

The heat shield is designed to protect the entire platform from direct solar radiation, particularly when Solar Orbiter will be at its closest to the Sun. At such times – when the solar distance is only 42 million km, or less than one third of Earth's distance from the Sun – the spacecraft will be subjected to about 13 times the amount of solar heating that Earth-orbiting satellites experience.

The heat shield comprises a series of physical barriers separated by two gaps, which allow lateral rejection of infrared radiation into the cold vacuum of space. The shield is attached to the Sun-facing side of the spacecraft by ten 1.5-mm thin "blades" made of titanium, which separate it from the rest of the orbiter.

|

| Solar Orbiter after installation of multi-layer insulation and heat shield. Credit: Airbus Defence and Space |

At the base of the heat shield is a 2.94 m × 2.56 m support panel that is about 5 cm thick. It is made of lightweight aluminium honeycomb with two carbon fibre skins that have very high thermal conductivity. The support panel is covered by 30 layers of low-temperature MLI that are able to withstand temperatures of up to 300 degrees Celsius. The insulation is designed to keep the support panel at temperatures below 150 degrees Celsius.

A series of ten star-shaped brackets attaches the support panel to an outer layer of high-temperature MLI, designed to withstand a temperature of up to 500 degrees Celsius. This state-of-the-art material is made of 20 very thin layers of titanium.

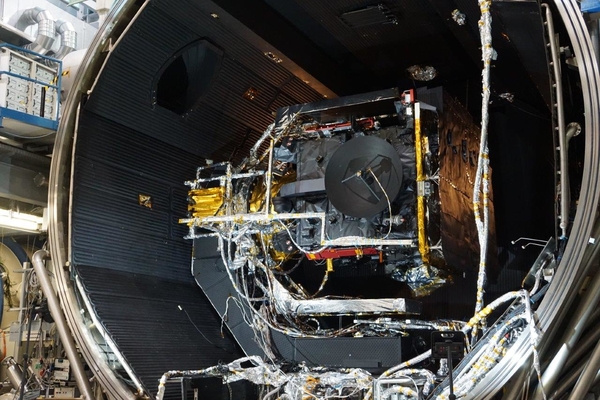

The first phase of environmental testing has begun in a special thermal-vacuum chamber in early December: there, powerful lamps are simulating the Sun's radiation.

|

| Solar Orbiter ready to enter the test chamber. Credit: Airbus Defence and Space |

The PFM thermal test is very similar to the one that was performed on the Structural Thermal Model (STM) in 2016. The main difference is that the STM test involved mock-ups of the spacecraft and heat shield, while the new test include the full flight hardware.

The initial phase of this first environmental test simulates the conditions that the spacecraft will undergo when it conducts a series of orbital manoeuvres en route to its operational orbit, for example during flybys of Earth and Venus.

"During 99% of the mission operations time, the heat shield will protect Solar Orbiter, but there will be more than a dozen manoeuvres when one of the side panels will be exposed to sunlight," said Claudio Damasio, ESA's Solar Orbiter project thermal engineer. "Therefore, we need to know how the Proto Flight Model responds when the exterior of the insulation on these panels reaches a temperature of about 120–150 degrees Celsius."

"At a later stage in the testing, we will rotate the Proto Flight Model so that its heat shield is facing the lamps, and we will then conduct hot and cold thermal balance phase tests to see if the spacecraft responds as expected. Subsequent hot and cold functional tests will take place with all of the instruments and units operating in the different flight modes."

The team plans to complete these thermal-vacuum tests before the end of December.

Various elements, such as the solar arrays and the instrument boom, are not yet included in the PFM and will be integrated after the thermal-vacuum tests are completed. The fully integrated spacecraft will then undergo a series of mechanical and electromagnetic compatibility tests early in 2019.

About Solar Orbiter

Solar Orbiter's mission is to perform unprecedented close-up observations of the Sun. Its unique orbit will allow scientists to study the Sun and its corona in much more detail than previously possible, and to observe specific features for longer periods than can ever be reached by any spacecraft circling the Earth. In addition, Solar Orbiter will measure the solar wind close to the Sun, in an almost pristine state, and provide high-resolution images of the uncharted polar regions of the Sun.

It will carry 10 state-of-the-art instruments. Remote sensing payloads will perform high-resolution imaging of the Sun's atmosphere – the corona – as well as the solar disk. Other instruments will measure the solar wind and the solar magnetic fields in the vicinity of the orbiter. This will give us unprecedented insight into how our parent star works, and how we can better predict periods of stormy space weather, which are related to coronal mass ejections (CMEs) that the Sun throws our way from time to time.

Scheduled for launch in February 2020, Solar Orbiter will take just under two years to reach its initial operational orbit, taking advantage of gravity-assist flybys of Earth and Venus, and will subsequently enter a highly elliptical orbit around the Sun.

Solar Orbiter is an ESA-led mission with strong NASA participation.