New Planck images trace cold dust and reveal large-scale structure in the Milky Way

17 March 2010

New images from ESA's Planck mission reveal details of the structure of the coldest regions in our Galaxy. Filamentary clouds predominate, connecting the largest to the smallest scales in the Milky Way. These images are a scientific by-product of a mission which will ultimately provide the sharpest picture ever of the early Universe.ESA's Planck microwave observatory – the first European mission designed to study the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) - has begun the second of four sky surveys, which will ultimately provide the most detailed information yet about the size, mass, age, geometry, composition and fate of the Universe. Although the primary goal of Planck is to map the CMB, by surveying the entire sky with an unprecedented combination of frequency coverage, angular resolution, and sensitivity, Planck will also provide valuable data for a broad range of studies in astrophysics. This is clearly demonstrated by new Planck images, published today, which trace cold dust in our Galaxy and reveal the large-scale structure of the interstellar medium filling the Milky Way.

|

|

New Planck images released today. For details, see below. |

Pinpointing the location of stellar formation

One of the key characteristics of Planck is its ability to measure the temperature of the coldest dust particles. Temperature is an important physical indicator as it reflects the balance of energies in the interstellar medium, and changes significantly from place to place, tracing the evolution of the star formation process.

|

|

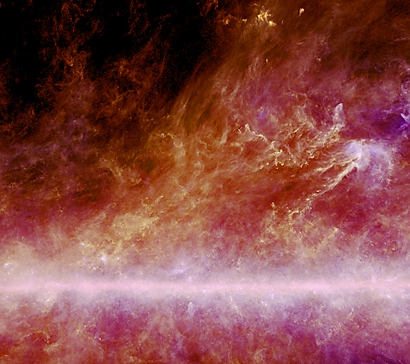

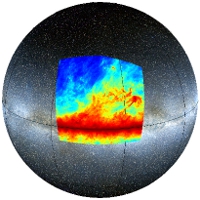

Planck images a galactic web of cold dust. |

Among the astrophysics-related investigations to be undertaken with Planck is a programme which aims to locate the coldest dusty clumps in the Galaxy, areas where star formation is about to occur. This image demonstrates how Planck traces this cold dust: reddish tones correspond to temperatures as cold as 12 degrees above absolute zero, and whitish tones to much warmer ones (of order a few tens of degrees) in regions where massive stars are currently forming. Planck excels at detecting these dusty clumps across the whole sky and contributes the crucial information required to measure accurately the temperature of dust at these large scales. By combining data from Planck with data from other satellites, such as Herschel or NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope (both of which probe the very small scales where star formation occurs), and IRAS (which has mapped the whole sky at shorter wavelengths) astronomers will be able to study the formation of stars across the entire Milky Way.

Filamentary structures permeate the cosmos

The space between stars is not empty but rather is filled with clouds of dust and gas - intimately mixed together - known as the 'interstellar medium'.

|

|

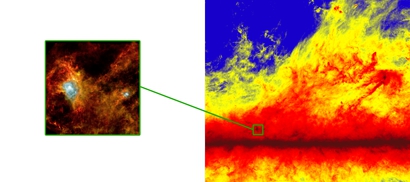

Filamentary structures are apparent at large-scales (as shown in this Planck image, on the right) and small-scales (as seen on the left, a Herschel image of a region in Aquila) in the Milky Way. |

The large clouds seen in this second Planck image (above, on the right), which covers a region of about 55 degrees across, show the filamentary structure of the interstellar medium in the solar neighbourhood (within about 150 pc, or 500 light years from the Sun). The local filaments are connected to the Milky Way, the horizontal feature at the bottom of the image, where the emission is coming from much larger distances across the disc of our Galaxy.

The image on the left shows a typical 'stellar nursery' (about 3 degrees across) in the Aquila constellation, as recently imaged by the Herschel Space Observatory. The filamentary structures seen at the smallest scales by Herschel are strikingly similar in appearance to those seen at the largest scales by Planck.

The richness of structure that is observed, and the way in which small and large scales are interconnected, provide important clues to the physical mechanisms underpinning the formation of stars and of galaxies. This example illustrates the synergy between Herschel and Planck; together these missions are imaging both the large-scale and the small-scale structure of our Galaxy.

|

The region of the sky covered by the Planck image is indicated on this image of half the sky. |

Editors notes:

Planck maps the sky in nine frequencies using two state-of-the-art instruments, designed to produce high-sensitivity, multi-frequency measurements of the diffuse sky radiation: the High Frequency Instrument (HFI) includes the frequency bands 100 – 857 GHz, and the Low Frequency Instrument (LFI) includes the frequency bands 30-70 GHz.

The first Planck all-sky survey began in August 2009 and is 98% complete (as of mid-March 2010). Because of the way Planck surveys the sky, the last bit of the first scan will be completed by late-May 2010. Planck will gather data until the end of 2012, during which time it will complete four sky scans. A first batch of astronomy data, called the Early Release Compact Source Catalogue, is scheduled for release in January 2011. To arrive at the main cosmology results will require about two years of data processing and analysis. The first set of processed data will be made available to the worldwide scientific community towards the end of 2012.

For further details please contact:

Jan Tauber, Planck Project Scientist

Research and Scientific Support Department,

Directorate of Science and Robotic Exploration

European Space Agency

Email: Jan.Tauber esa.int

esa.int