Venus Express shows off new findings at major conference

22 June 2010

Thanks to data from Venus Express we have the best idea yet of how Venus' atmosphere works, but there is still a long way to go, delegates at this year's International Venus Conference will be told. At the event, taking place this week (20-26 June) in Aussois, France, scientists are outlining how a better understanding of our nearest planetary neighbour can help us probe our own planet, as well as other bodies in our Solar System, and beyond.

|

|

Venus Express Credit: ESA |

To redress the balance, and attempting to pin down Venus' atmospheric secrets, ESA launched Venus Express – its first spacecraft to the second planet from the Sun - in November 2005. Arriving in April 2006, the mission has scrutinised Venus ever since and its latest findings are the subject of this year's conference, an event that excites Venus Express Project Scientist Håkan Svedhem. "After four years Venus Express continues to provide a rich source of data and information, and this year's conference will see some of the most interesting findings yet," he said.

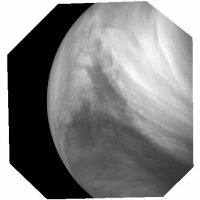

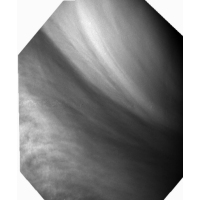

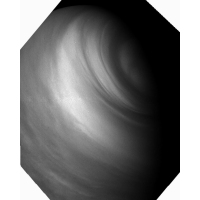

Amongst Venus Express' strengths is the ability to provide multi-wavelength imaging and spectroscopic observations of the planet's atmosphere and clouds, allowing researchers to build up a comprehensive picture of their structure, composition and dynamics. In Aussois, new images from the Venus Monitoring Camera (VMC) will be presented showing, for the first time, mesoscale, regional views of the planet. This marks a departure from the global views of the planet that have been available until now. "These new images clearly highlight the variation in dynamical behaviour across the planet, and with these we can now start to track the transport of momentum in the cloud tops," notes Dmitriy Titov, from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany. "I expect that this will be a key factor in contributing to understanding the phenomenon of super-rotation," he adds. Understanding the origin of atmospheric super-rotation – the 'mismatch' in rotation speeds between the cloud tops and the planet surface – is one of the goals of the Venus Express mission.

In addition to these spectacular new images, 3-D temperature maps calculated from Venus Express' Visual and Infra-red Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) will be presented, covering Venus' night-side between altitudes of 65-96 km. "This is fundamentally important to understanding what is happening as temperature fluctuations drive a number of separate processes which affect the energy budget of the atmosphere," says Davide Grassi of IFSI-INAF in Rome. The 3-D temperature maps being presented by Grassi and his colleagues suggest the presence of atmospheric thermal tides as well as providing a rich data source for other scientists.

However, this work is limited to the night-time regions of the southern hemisphere due to interfering infra-red emission from the day-side and Venus Express' orbital orientation. To extend the picture further, a separate team will present the latest incarnation of their General Circulation Model (GCM), a theoretical account of the Venusian atmosphere from ground-level up to 100 km.

Traditionally, models of the Venusian atmosphere have started with our own planet. "Previous models took the Earth, removed the oceans and Earth's mountains and replaced them with Venus' mountain ranges, as well as specifying temperature and solar heating profiles representative of Venus," explains Colin Wilson, of Oxford University, who uses VIRTIS to study Venus' atmospheric dynamics. This new model, led by Sébastien Lebonnois of the Laboratoire de Métérologie Dynamique in Paris, has gone a step further and accounted for infrared heat transfer within the atmosphere, which is especially important for a dense atmosphere such as that found on Venus. "In our model we have developed a radiative transfer scheme that can compute the temperature consistently in the GCM; this is the main difference between previous work and what we've done," said Lebonnois.

Wilson believes the GCM provides "our best idea yet of what is going on in Venus' atmosphere, as it agrees with many observations from Venus Express." "Lebonnois' model is possibly the most realistic to date, because it includes radiative transfer," he added. However, whilst the proposal goes a long way to accounting for our observations of Venus' atmosphere, even Lebonnois admits he's not there yet. "The problem is, for the moment, that our work doesn't include photochemistry. We didn't test this in our model yet, this is an ongoing project," he explained.

As theorists like Lebonnois chisel at their models to make them agree more with what missions such as Venus Express observe, Venus can be used to understand more about other worlds. "Understanding the evolution of Venus should help us understand not only the evolution of the Earth but perhaps even extrasolar planetary systems as well," says Wilson. Lebonnois sees parallels between Venus and Titan, Saturn's largest moon. "Titan also has a super-rotating atmosphere. We can study both systems and see whether the same mechanisms are playing the same role or not. This can help to build a global picture of the forces that dictate how an atmosphere evolves," he explained.

|

|

JAXA's Akatsuki, Venus Climate Orbiter |

These joint observations are among the many topics being discussed at the meeting at Aussois. With almost one hundred presentations due at the International Venus Conference this week, Venus science is set to make great progress.

Notes for editors:

The International Venus Conference is taking place 20-28 June, 2010, at Aussois, France. This is the third in a series of conferences focussing on the science results from Venus Express; the previous two meetings were held in La Thuile, Italy, as "Rencontres de Moriond". The results presented at the International Venus Conference will be published in a special issue of the Icarus journal.

ESA's Venus Express and JAXA's Akatsuki missions are complementary in many ways: The Japanese mission’s near-equatorial orbit allows it to focus on low-latitude regions, while Venus Express’s polar orbit has led it to focus on high-latitude regions. Akatsuki’s cameras will study the movement of features at a range of altitudes, while the spectrometers in the Venus Express payload can provide more detailed analyses of the atmospheric regions being imaged by Akatsuki. Finally, a lightning detection camera on Akatsuki will try to take the first ever pictures of lightning on Venus; the existence of lightning has been inferred from magnetic field observations by Venus Express.

Contacts:

Håkan Svedhem, Venus Express Project Scientist

Directorate of Science and Robotic Exploration

European Space Agency

Email: hsvedhem rssd.esa.int

rssd.esa.int