Pioneering Philae completes main mission before hibernation

15 November 2014

Rosetta's lander has completed its primary science mission after nearly 57 hours on Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

|

|

Philae's first touchdown seen by Rosetta's NavCam. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 |

After being out of communication visibility with the lander since 09:58 GMT / 10:58 CET on Friday, Rosetta regained contact with Philae at 22:19 GMT / 23:19 CET last night. The signal was initially intermittent, but quickly stabilised and remained very good until 00:36 GMT / 01:36 CET this morning.

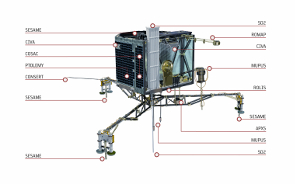

In that time, the lander returned all of its housekeeping data, as well as science data from the targeted instruments, including ROLIS, COSAC, Ptolemy, SD2 and CONSERT. This completed the measurements planned for the final block of experiments on the surface.

|

|

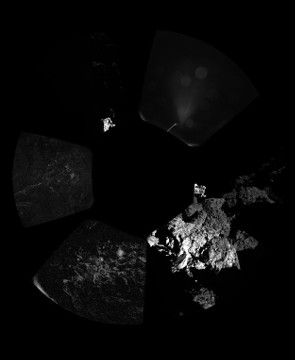

First comet panoramic image. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA |

In addition, the lander's body was lifted by about 4 cm and rotated about 35° in an attempt to receive more solar energy. But as the last science data fed back to Earth, Philae's power rapidly depleted.

“It has been a huge success, the whole team is delighted,” said Stephan Ulamec, lander manager at the DLR German Aerospace Agency, who monitored Philae’s progress from ESA’s Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, this week.

“Despite the unplanned series of three touchdowns, all of our instruments could be operated and now it's time to see what we've got.”

Against the odds – with no downwards thruster and with the automated harpoon system not having worked – Philae bounced twice after its first touchdown on the comet, coming to rest in the shadow of a cliff on Wednesday 12 November.

The search for Philae's final landing site continues, with high-resolution images from the orbiter being closely scrutinised. Meanwhile, the lander has returned unprecedented images of its surroundings.

While descent images show that the surface of the comet is covered by dust and debris ranging from millimetre to metre sizes, panoramic images show layered walls of harder-looking material. The science teams are now studying their data to see if they have sampled any of this material with Philae's drill.

|

|

Philae's instruments. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab |

“We still hope that at a later stage of the mission, perhaps when we are nearer to the Sun, that we might have enough solar illumination to wake up the lander and re-establish communication,” added Stephan.

From now on, no contact will be possible unless sufficient sunlight falls on the solar panels to generate enough power to wake it up. The possibility that this may happen later in the mission was boosted when mission controllers sent commands to rotate the lander's main body with its fixed solar panels. This should have exposed more panel area to sunlight.

The next possible communication slot begins on 15 November at about 10:00 GMT / 11:00 CET. The orbiter will listen for a signal, and will continue doing so each time its orbit brings it into line-of-sight visibility with Philae. However, given the low recharge current coming from the solar panels at this time, it is unlikely that contact will be re-established with the lander in the near future.

|

|

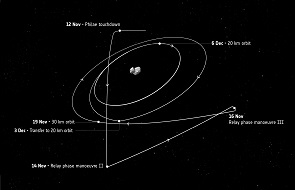

Rosetta's trajectory after 12 November. Credit: ESA |

Meanwhile, the Rosetta orbiter has been moving back into a 30 km orbit around the comet.

It will return to a 20 km orbit on 6 December and continue its mission to study the body in great detail as the comet becomes more active, en route to its closest encounter with the Sun on 13 August next year.

Over the coming months, Rosetta will start to fly in more distant 'unbound' orbits, while performing a series of daring flybys past the comet, some within just 8 km of its centre.

Data collected by the orbiter will allow scientists to watch the short- and long-term changes that take place on the comet, helping to answer some of the biggest and most important questions regarding the history of our Solar System. How did it form and evolve? How do comets work? What role did comets play in the evolution of the planets, of water on the Earth, and perhaps even of life on our home world.

“The data collected by Philae and Rosetta is set to make this mission a game-changer in cometary science,” says Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta project scientist.

Fred Jansen, ESA's Rosetta mission manager, says, “At the end of this amazing rollercoaster week, we look back on a successful first-ever soft-landing on a comet. This was a truly historic moment for ESA and its partners. We now look forward to many more months of exciting Rosetta science and possibly a return of Philae from hibernation at some point in time.”

More about Rosetta

Rosetta is an ESA mission with contributions from its Member States and NASA. Rosetta’s Philae lander is provided by a consortium led by DLR, MPS, CNES and ASI.