Klim Churyumov - co-discoverer of comet 67P

After a 10-year voyage around the Solar System, the Rosetta spacecraft successfully reached comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on 6 August 2014.

Named after its two co-discoverers, the periodic comet has been revealed as a rugged, double-lobed structure with a 'head' and a 'body' separated by a narrow neck. For more than two years, from arrival until the Rosetta mission ended with the controlled impact of the orbiter on the comet, ESA's comet chaser undertook the most intimate examination ever made of one of these ancient planetary building blocks.

Professor Klim Churyumov followed the historic exploits of Rosetta and its small Philae lander with particular interest until he passed away in October 2016. He was one of the researchers who, with Svetlana Gerasimenko, first saw the comet 45 years ago.

Klim was born in Nikolaev, Ukraine. Among his earliest memories are stories that his elder brother, Ivan, told to Klim, his brother Semyon, and sister, Galina. These were about philosophy, travel and ancient cultures. They also included tales about the constellations that they could see as the siblings lay on the roof of their shed and watched the night sky overhead.

|

| Klim Churyumov pictured with Robert Sheckley in Kiev, 2005. Image courtesy K. Churyumov. |

During his early years, Klim was inspired by science fiction stories and he read widely, including books by the renowned author Robert Sheckley. Years later, Klim met the author and was delighted to have the opportunity to tell him about the Rosetta mission.

Klim was an outstanding student, eventually entering Kiev University to study physics. During his third year, he was disappointed to be assigned to the faculty of optics, instead of theoretical physics. However, he continued to attend lectures on theoretical physics, even though the authorities disapproved, and he was eventually moved to the faculty of astronomy, where there were vacant places. Although it had not been his original choice, it turned out to be a fortunate move.

"I never regretted being moved to the faculty of astronomy," he wrote many years later.

Over the following years he began to study the physics of comets, under the tutelage of Professor Sergej K. Vsekhsvyatskij, a well-known comet researcher. At first, this involved using the telescopes of the astronomical observatory of Kiev University. Further research was undertaken from observatories in the southern Soviet Union - Azerbaijan, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Crimea and, particularly, Alma-Ata (Kazakhstan).

In 1969, Klim discovered the object which was later to become the target for ESA's Rosetta mission. At the time, he was leading an expedition to the observatory of the Institute of Astrophysics in Alma-Ata, along with Svetlana Gerasimenko and Ludmila Chirkova, a photographic laboratory assistant.

Using a Maksutov telescope, they set out to observe known comets and search for newcomers. This involved exposing two photographic plates to the same part of the sky, with an interval of 20-30 minutes between exposures. By comparing the images, it was possible to find new comets moving across the background of 'fixed' stars.

The first plates taken on 9 September included comet 32P/Comas Solà. However, follow up observations were delayed by bad weather. Two days later, Svetlana and Ludmila were able to photograph the region of the sky that included Comas Solà, but a processing error meant that one of the plates was underdeveloped - the sky in the centre of the plate was lighter than at the edges. Despite the faulty development of the plate it was possible to discern a small diffuse spot.

At first it was assumed that the spot was comet Comas Solà or a photographic defect, and Svetlana wanted to throw the plate away. However, Professor Dmitri Rozhkovsky told her to keep it, noting that useful information may be found even on defective plates. Svetlana and Ludmila returned to Kiev, while Klim stayed behind to take some more observations.

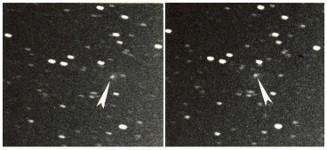

|

|

| Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (indicated by the arrows), 21 September 1969. Image courtesy K. Churyumov. | Klim Churyumov and Svetlana Gerasimenko in Dushanbe, 1975. Image courtesy K. Churyumov. |

When they eventually began measuring the positions of all the photographed comets, they calculated that the diffused spot on the defective plate taken on 11 September was almost two degrees from the position of Comas Solà. When they looked at the other plates, Klim and Svetlana were delighted to find four more images of the new object. They had discovered a new comet, which was subsequently named 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. This comet is now known to be a short-period Jupiter Family comet.

Klim went on to discover another comet in 1986, in collaboration with astronomer Valentin Solodovnikov. This comet – named C/1986 N1 (Churyumov-Solodovnikov) - was making its first passage through the inner Solar System.

|

| Klim Churyumov (left) with S.P. Kapotza, 1986. Image courtesy K. Churyumov. |

During his long and successful career, Klim has enjoyed reaching out to wider audiences, appearing on Kiev TV to speak about astronomy, as well as writing some 1000 popular scientific articles and seven popular science books – most recently co-authoring one entitled "Comet-asteroid danger: reality and myths".

At one time he was a keen sportsman: his activities included skydiving, swimming, football, table tennis and chess. He has also been writing poetry since he was 16 years old and several books of his poems for children were published in the period 1999 to 2002.

He has won numerous awards and medals for his scientific work, and was chosen as a Corresponding Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in 2006.

Klim continues to study comets, in particular their spectra, which give a breakdown of the objects' compositions. Of course, he is especially interested in the Rosetta mission.

"I have been following every step of Rosetta since 2003, when our comet was chosen as its main target," he said.

"I was invited to the international conference in Capri, entitled 'New Rosetta Targets', where I made a report on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. There I met Helmut Rosenbauer, the Director of the Max Planck Institute in Lindau, Germany, who led the development of the Philae lander. I also met many of the mission scientists who designed and implemented the highly accurate and highly sensitive instruments on Rosetta and Philae.

"Svetlana and I were able to attend the launch of Rosetta in 2004. I am hoping to be able to watch in real time the most important manoeuvre of the mission, the landing of Philae on the comet's nucleus.

"After the Rosetta mission comes to an end, there will be a unique archive of data on the comet 67P," he said. "There will be a lot of mysteries that will need to be solved and I would like to participate in this research."

Klim was a passionate advocate of the importance of studying comets.

"There are many reasons why the study of comets is of value. First, comets are 'time capsules', since they retain the primary substances that existed during the birth of the Sun and planets 4.6 billion years ago," he said. "Second, they are indicators of physical conditions in interplanetary space.

"Third, comets are natural space laboratories with unique physical phenomena which cannot be reproduced in laboratories on Earth. Fourth, there is a possibility that a comet nucleus will collide with Earth, causing a global catastrophe like the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago."

|

| Svetlana Gerasimenko and Klim Churyumov in Kiev, 2002. Image courtesy of K. Churyumov. |

Klim remained in touch with Svetlana Gerasimenko, mostly via the Internet, although they would try to catch up when she came back to Kiev from her research base in Tajikistan.

Rosetta is a mission that has caught the attention of the public, and many young people followed the mission via social media channels like Twitter and Facebook. When asked what advice he would give to young people who are thinking of taking up science as a career, Klim replied:

"When young people decide to take up science as a career, they have to be prepared to be hard working and persistent (in trying to achieve their goals). They need inspiration and devotion to the branch of science they chose. If they choose one of the physical sciences, they have to possess skills in mathematics and programming, and they have to put forward interesting and sometimes fantastic ideas, creating new models.

"They must never allow difficulties stop them. Everybody, even the most talented scientist, has difficult moments in their career, but only persistence and hard work can help to find the solution for any problem. Scientists should aim to perfect their knowledge of mathematics, physics, chemistry and other branches of the natural sciences in order to broaden their general knowledge. All that, sooner or later, will help to find the solution for the problem in hand. I wish young scientists good luck and inspiration!"

Klim Churyumov was interviewed by Peter Bond in summer 2014. We acknowledge the assistance of Natalja Porlinskaya with translations.