Biomarker found in space complicates search for life on exoplanets

2 October 2017

A molecule once thought to be a useful marker for life as we know it has been discovered around a young star and at a comet for the first time, suggesting these ingredients are inherited during the planet-forming phase. |

| Comet 67P/C-G in May 2015. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 |

The discovery of methyl chloride was made by the ground-based Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, and by ESA's Rosetta spacecraft following Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. It is the simplest member of a class of molecules known as organohalogens, which contain halogens, such as chlorine or fluorine, bonded with carbon.

Methyl chloride is well known on Earth as being used in industry. It is also produced naturally by biological and geological activity: it is the most abundant organohalogen in Earth's atmosphere, with up to three megatonnes produced a year, primarily from biological processes.

As such, it had been identified as a possible 'biomarker' in the search for life at exoplanets. This has been called into question, however, now it is seen in environments not derived from living organisms, and instead as a raw ingredient from which planets could eventually form.

This is also the first time an organohalogen has been detected in space, indicating that halogen- and carbon-centred chemistries are more intertwined than previously thought.

The ALMA observations were made towards the young star IRAS 16293-2422, a low-mass binary system in the Rho Ophiuchi star-forming region about 400 light-years from Earth. The system was already known to have a wealth of organic molecules distributed around it, but ALMA now makes it possible to zoom in to scales equivalent to the outer planets in our own Solar System, making it an ideal target for comparative studies with comets.

|

| Rho Ophiuchi star-forming region. Credit: ESA/Herschel/NASA/JPL-Caltech, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO; Acknowledgement: R. Hurt (JPL-Caltech) |

Because comets are believed to preserve the chemical composition of the Sun's birth cloud, and in order to better understand the formation pathways of organic molecules, the detection of the molecule in the young star system triggered a search in the extensive data collected by ESA's Rosetta spacecraft during its 2014–16 mission at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

"We found it but it is very elusive, one of the 'chameleons' of our molecule zoo, only present during short times when we observed a lot of chlorine," says Kathrin Altwegg, principal investigator of the ROSINA instrument that made the comet detection.

The measurements were made in May 2015, when the comet was approaching its closest point to the Sun along its elliptical orbit, near to the orbit of Mars, and was very active, releasing a lot of gas and dust as the Sun warmed its icy surface. The methyl chloride was identified in the measurements when the hydrogen chloride signal was at its highest.

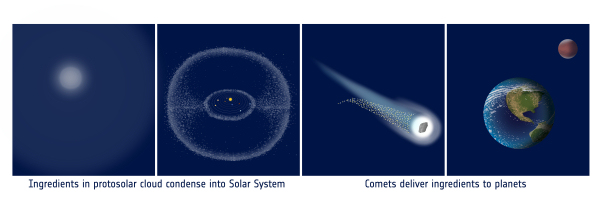

Moreover, the methyl chloride was found in comparable abundances in both the young star system and the comet. Rocky planets like Earth could directly inherit these ingredients during the planet-building phase, but comets could also act as a vessel to deliver them through the high rate of impacts occurring in the early years of a forming solar system.

|

| Delivering ingredients to Earth. Credit: ESA |

"The dual detection of an organohalogen in a star-forming region and at a comet indicates that these chemicals will likely be part of the 'primordial soup' on the young Earth and newly formed rocky exoplanets," says Edith Fayolle, lead author of the study published in Nature Astronomy. "Understanding this initial chemistry on planets is an important step toward the origins of life."

It is also a crucial aspect for the search for life outside our Solar System, but the apparent prevalence of organohalogens in space calls into question their use as a biomarker when interpreting possible future detections of the molecule in the atmospheres of rocky exoplanets.

"The combined study takes detections of key biological molecules to a new level, with the exciting possibility that they predate the formation of our Solar System as we know it today," comments Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta Project Scientist.

"The complementary results provide an important context for our Rosetta data and for the wider implications of Solar System formation, and especially how we might interpret observations of extrasolar systems."

Notes for Editors

"Protostellar and cometary detections of organohalogens," by E. Fayolle et al. is published in Nature Astronomy, 2 October 2017.

The ALMA data were part of the Protostellar Interferometric Line Survey (PILS). The aim of the survey is to chart the chemical complexity of IRAS 16293-2422 by imaging the full wavelength range covered by ALMA on very small scales, equivalent to the size of our Solar System.

ALMA is an international astronomy facility, and a partnership between the European Southern Observatory, the US National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences of Japan in collaboration with the Republic of Chile. More about ALMA partners.

For further information, please contact:

Edith Fayolle

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (now at NASA JPL)

Email: edith.c.fayolle![]() jpl.nasa.gov

jpl.nasa.gov

Kathrin Altwegg

University of Bern, Switzerland

Email: kathrin.altwegg![]() space.unibe.ch

space.unibe.ch

Matt Taylor

ESA Rosetta Project Scientist

Email: matt.taylor![]() esa.int

esa.int

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer![]() esa.int

esa.int